We have decided to dedicate this year’s seminar series to the theme of Constitutio libertatis, the famous expression used by Hannah Arendt to define the essential counterpart of any revolution that aspires to be truly democratic—namely, the constitution of freedom, which takes shape through the establishment of a new power and a new political body.

The political categories we have used from modernity to the present to codify the relationship between political forces and institutions are increasingly revealing their inexorable inability to capture the present. At least within the context of Western liberal democracies, we have been accustomed to thinking that reactionary and conservative forces identified themselves with the ultimate goal of maintaining—of “conserving,” in fact—the status quo, the established order in terms of traditions and institutions, in order to ward off the specter of change at all costs. On the other hand, progressive forces saw themselves as advocates of the need for transformation, in some cases even radical and revolutionary, of institutions.

As Arendt wrote in one of her most famous and explicitly political works, On Revolution (1963), participants in political debate were traditionally divided into “radicals, who recognized the fact of revolution without understanding its problems, and conservatives, who clung to tradition and the past as fetishes to ward off the future.” Today, however, this framework no longer seems to hold.

In recent years, both in Europe and overseas, reactionary political forces have come to define themselves through an unabashed attack on institutions, and they are the ones now advocating radical change in the name of a new order—often dangerously anti-democratic. Meanwhile, progressive forces have found themselves facing a task for which they were evidently unprepared: defending institutions, protecting democratic traditions and hard-won rights. The loss of electoral support for much of the left, in Europe and beyond, highlights the difficulty of assuming this role, which, to be effective, should manage to defend established democracy without giving up the possibility of transforming it. This entails reconciling what, in modern and contemporary political thought, sounds almost like an oxymoron: stability and change, the legacy of tradition and the birth of the new, or, as Arendt puts it, “the concern for stability and the spirit of novelty.”

In light of this difficult and urgent issue, which troubles both political theory and practice, we have decided to dedicate this year’s seminar series to the theme of Constitutio libertatis, the famous expression Arendt uses to define the indispensable counterpart of any revolution that aspires to be truly democratic: the constitution of freedom, which takes shape in the establishment of a new power and a new political body—or, in her words, a “political space that possesses power and is authorized to claim rights without possessing or asserting sovereignty.” This very renunciation of sovereignty—of a transcendent, metaphysical, or divine source of political authority—is at once the core of every democratic institution and the reason it is continually confronted with the problem of durability or, in Arendtian terms, the “permanence” of the foundation, since the latter no longer rests on an eternal and absolute principle. Through the idea of Constitutio libertatis, Arendt invites us to rethink this relationship between foundation and stability, between the new and the established—not as opposing concepts (a habitual mode of thought that has long shaped political theory) but rather as correlative aspects of the very process of democratic institution-building.

The aim of our reflections will be, in particular, to bring together the genuinely political nature of Constitutio libertatis with its juridical counterpart. While it is true that Arendt did not develop a systematic philosophy or theory of law, her reflections on the intertwining of politics and law, power and legislation, and the relationship between the authentically political and the strictly juridical dimensions of democratic constitutionalism are present throughout much of her work. From The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951), where she analyzes the rise of Nazism starting from the usurpation of legal personality and criticizes the abstraction of human rights, counterposing them with “the right to have rights,” to The Human Condition (1958), where she considers the law of the polis as that which protects and includes political space, significantly defining it as “a wall, without which there might have been a collection of houses, a village, but not a city, a political community.” Then there are her reflections on the distinction between the Greek nomos and the Roman lex and the latter’s fundamental legacy for the development of European constitutional law, which resurface in both On Revolution (1963) and the unfinished Introduction into Politics (whose notes are now published in What Is Politics?). The analysis of the judiciary and its limits in Eichmann in Jerusalem (1963), her studies on the constituent act and its connection to freedom and public happiness, and finally her argument that civil disobedience is the best remedy for the failure of constitutional review mechanisms and that protest groups should be given a constitutional role (Civil Disobedience, 1972).

These legal aspects of Arendt’s work and their implications for political institutions have so far received only limited attention in both international and Italian scholarship (notable exceptions include Arendt and the Law [Hart Publishing, 2012], edited by Marco Goldoni and Chris McCorkindale, and Christian Volk’s Arendtian Constitutionalism: Law, Politics, and the Order of Freedom [Hart Publishing, 2015]). In an attempt to fill this gap, this seminar series aims to trace Arendtian paths through law and institutions. Our approach will, so to speak, be circular: we will begin and conclude with Arendt—first recovering the strictly legal dimension of Constitutio libertatis, and then returning to her reflections on the relationship between freedom, revolution, and constitution, which define her model of participatory and council democracy. In between, we will juxtapose Arendt’s theory with that of other contemporary thinkers who have engaged with the problem of institutions, from Max Weber’s sociology to Merleau-Ponty’s philosophy and Yan Thomas’s legal theory, to explore both continuities and divergences.

Each session will thus invite reflection on the practical and theoretical meaning of institution-building and the urgent need to reimagine and renew our commitment to the institutional space of democracy. Seen through the Arendtian lens, this space is no longer merely a site of control and power but rather a place for collective action, for participating with others to voice plural needs. Reflecting on this lost dimension of institution-building as a collective and plural practice seems more urgent than ever in order to overcome the indifference—or even suspicion—that institutions provoke in many citizens today. Our task, therefore, is to interrogate, once again bridging theory and praxis, how democratic institutions can be transformed from something distant and alien to our private concerns into practices and spaces to be collectively cared for. This ambition is not as utopian as it might initially seem: we need only think of the crowded squares of recent years, from Kyiv to Tbilisi, reminding old Europe and its dormant citizenry that democracy is, above all, an institution of freedom—one that must be won and defended continually.

With this in mind, moving between philosophy, politics, and law, we will explore the increasingly urgent question of how to bring forth the new in the political sphere while also providing it with the necessary tools to endure and defend itself against the relentless attacks that undermine the very foundations of democratic freedom.

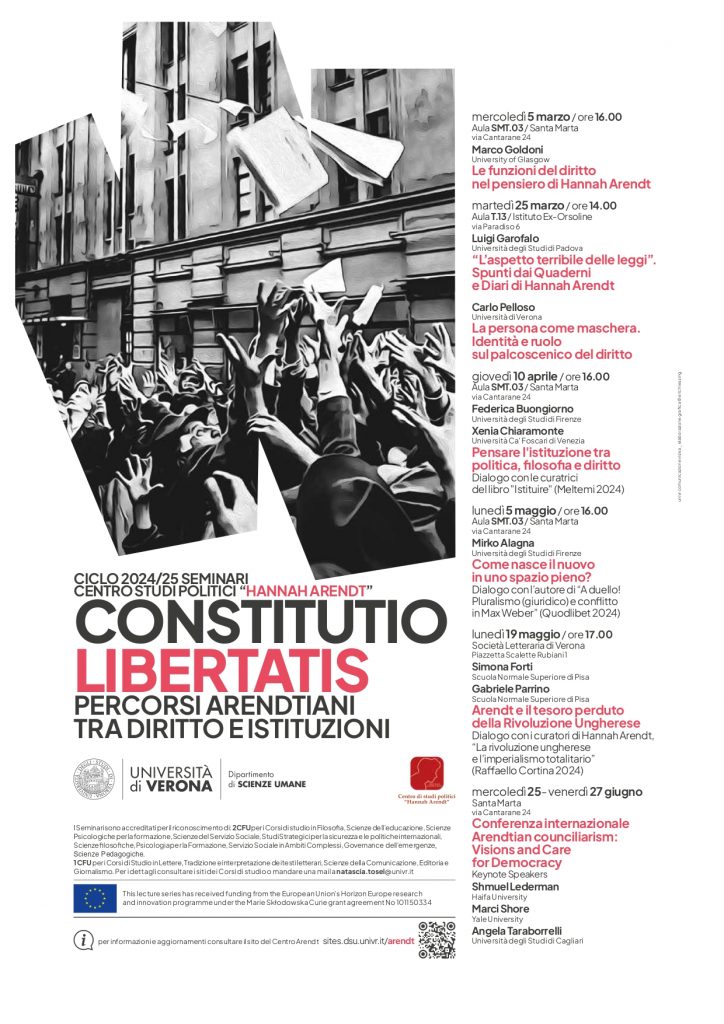

Seminar Schedule:

- March 5:

Marco Goldoni (University of Glasgow) – The Functions of Law in Hannah Arendt’s Thought - March 25:

Luigi Garofalo (University of Padua) – The Terrifying Aspect of Laws: Insights from Arendt’s Notebooks and Diaries

Carlo Pelloso (University of Verona) – The Person as a Mask: Identity and Role on the Legal Stage - April 10:

Federica Buongiorno (University of Florence) & Xenia Chiaramonte (Ca’ Foscari University, Venice) – Thinking Institutions Between Politics, Philosophy, and Law - May 5:

Mirko Alagna (University of Florence) – How Does the New Emerge in a Crowded Space? - May 19:

Simona Forti & Gabriele Parrino (Scuola Normale Superiore, Pisa) – Arendt and the Lost Treasure of the Hungarian Revolution - June 25-27:

International Conference: “Arendtian Counciliarism: Visions and Care for Democracy”

Keynote Speakers: Shmuel Lederman (Haifa University), Marci Shore (Yale University), Angela Taraborrelli (University of Cagliari)

We look forward to seeing many of you there!

You can find all the details regarding each session and the accreditation of 2 CFU on the official flyer: Constitutio Libertatis. Percorsi arendtiani tra diritto e istituzioni

The full description of the lecture series is available here: Abstract Constitutio Libertatis